It’s 9.30pm NZ time when Dr Jane Goodall and I connect over Zoom and I’m lucky to get a time slot on her busy calendar.

Goodall is punctual, jumping into the call a minute early. She’s already had a busy morning and after speaking with me is off to record two back-to-back videos before getting stuck into her inbox heaving with more than 3000 “recent” emails.

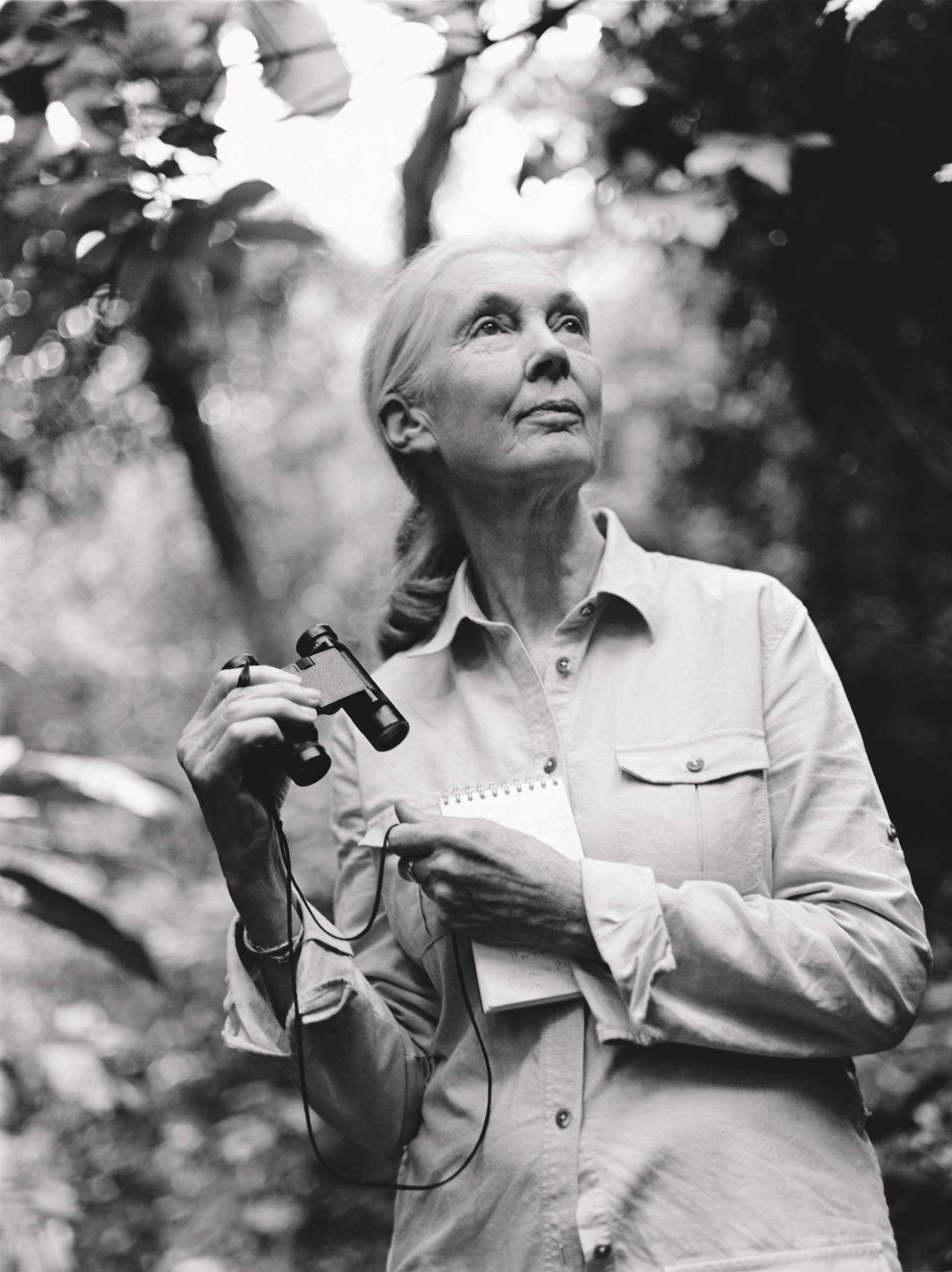

Having recently celebrated her 90th birthday I’m keen to learn her secret to health, longevity and energy. What wellbeing practices does she follow?

“I don’t do anything for my health,” she says matter-a-fact. “My son says, ‘I don’t know anybody who eats so little and so badly and has so much energy.’ I just go. Since I got back from the last two-and-a-half-month tour to Africa, Europe, America and Canada I haven’t even had time for a walk. I’ve just been frantically trying to catch up.”

Goodall travels an average of 300 days per year to visit schoolchildren and speak to packed auditoriums. She spent her birthday on April 3 in New York working and attending a fundraising gala dinner, and while she’s not a fan of galas, she is committed to the cause.

Recent NZ tour

On her recent visits to Auckland and Wellington as part of her Reasons for Hope global tour in June, she delivered a lecture and was joined on stage in Auckland for a Q&A with sustainable skincare entrepreneur Emma Lewisham, whose brand she endorses, and in Wellington with chief executive of Te Nukuao Wellington Zoo, Karen Fifield.

“It’s important to be talking about hope because if we lose hope, we become apathetic, we do nothing and if we don’t get together and do something about the state of the world, well, we’re doomed, so I’m trying to wake people up and say, ‘Do something, anything, but do something for the poor old planet’.”

A UN Messenger of Peace, Goodall believes in hope. Having lived through the Second World War she’s been witness to hopelessness at a time when there was no way that Britain, which was standing alone in Europe, could withstand the might of Nazi Germany. “We weren’t even prepared for war, but we had Churchill,” she says. “I’ve lived through a hopeless time and came out of it. We’re in another bad time and we can, if we want to, climb out again.

“The most important thing for people to realise is that their lives do matter, and they can make a difference. Too many people say, ‘what can I do? I’m just one person?’. Yes, you are one person but it’s not just you who feels like that. So, pull yourself together and get out there and do something and get your friends to join you. That’s where kids do so well. They get out there, take action and see that they make a difference and that gives them inspiration to want to do more and that inspires others, including parents.”

Recently a CEO at a conference in Singapore she attended shared with her how he’d spent the past eight years working to get his company more ethical and sustainable after his 10-year-old daughter came home from school and asked, ‘Daddy, they tell me that what you’re doing is harming the planet. That’s not true is it? Because it’s my planet’.”

Taking action

“I think everybody has to realise that every day they live they make some impact and certainly the readers of this magazine will be able to choose what kind of impact they make and what people should get involved in is something they care about. It’s no good me saying, ‘you should do this or that or the other’. People will only really take action with energy and enthusiasm if it’s something they personally care about.”

On a personal level Goodall tries to think about the footprint she leaves each day, like turning off the lights and picking up trash if she sees it. She also makes an effort not to be wasteful and gets 15 cups out of her coffee filter papers rather than tossing them out after each use.

“If 10 million people remember to always turn lights off, that saves masses of electricity, and it’s the same with picking up trash,” she says. “Everyone can make a difference in their own way. They just need to think about it and make certain changes to their lifestyle. It can include things like writing letters to politicians or especially choosing what to buy and what not to buy because that can lead to consumer pressure and that’s already changing the way some businesses act.”

Voice for biodiversity

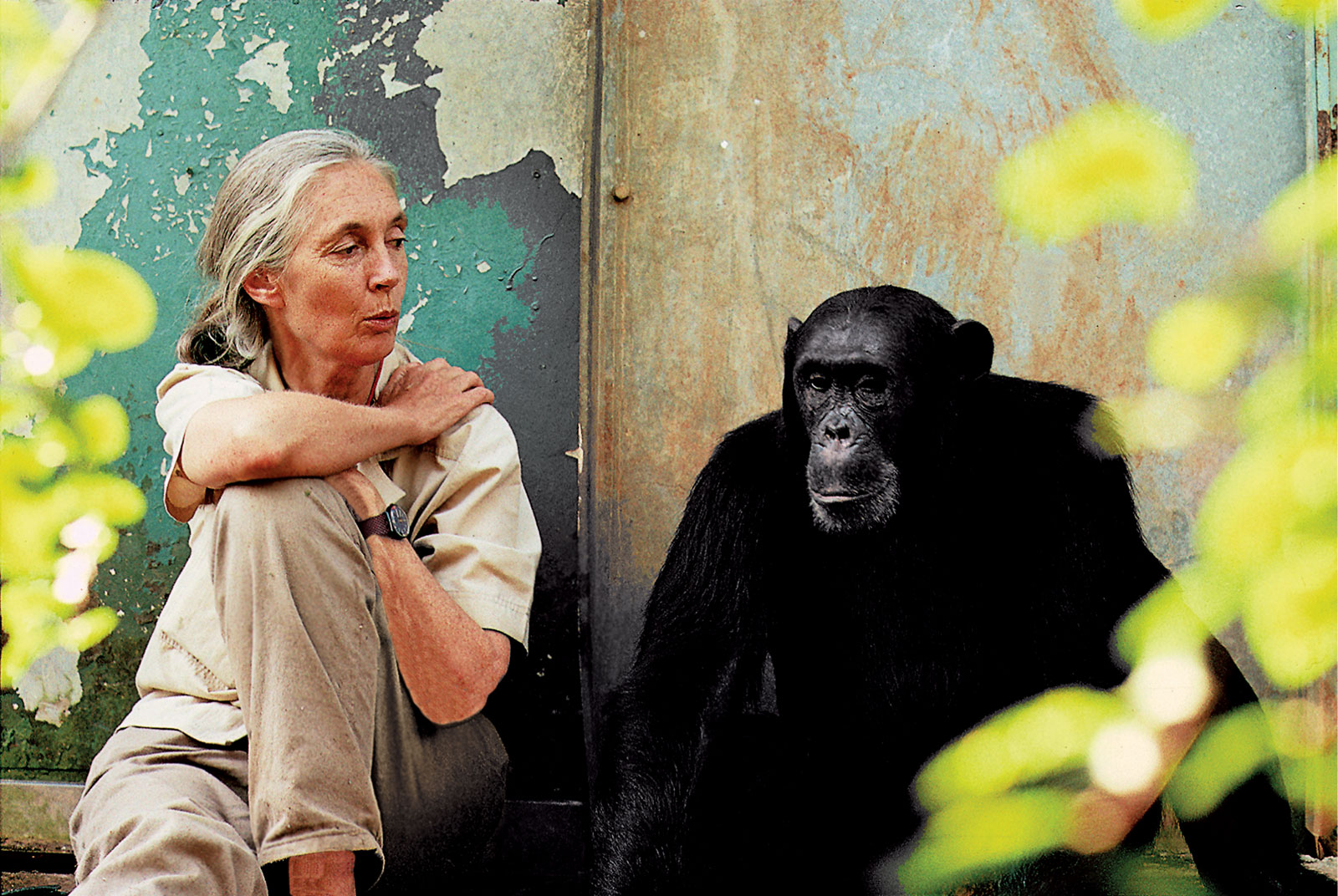

Best known for her ground-breaking study of chimpanzees which began in 1960, Goodall has long been a champion of chimps and the natural world.

Her ability to raise public awareness and understanding became instrumental in her work to save chimpanzees from extinction.

“It’s not just climate, it’s also loss of biodiversity. They go together. We’re not separate from the natural world. People have this idea that there’s humans, cities and then there’s the natural world out there. We’re actually part of it and not only that, we depend on it for food, water and air. What we depend on is healthy ecosystems and an ecosystem is that complex mix of birds, animals, plants and fungi. I see it like a tapestry and every time a species goes from that ecosystem, it’s as though you pull a thread from that beautiful tapestry. If enough threads are pulled, the tapestry will hang in tatters and the ecosystem will collapse.”

Loss of biodiversity, she explains, is hastened up by climate change and because an ecosystem is destroyed and desertified, that adds to climate change and so they are interlinked.

Growing up

Goodall was born with a love of animals and nature. She spent her childhood out in nature or reading books because television hadn’t been invented and there was no social media.

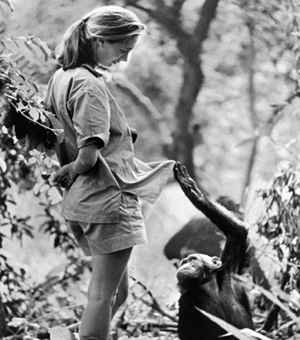

Back in 1960 when she had the opportunity to study the animals most like us, chimpanzees, science believed that only humans had personalities, minds and emotions. In this respect she knew these erudite professors were totally wrong because of her teacher. Her dog Rusty.

Her observations proved that chimpanzees like humans make and modify tools and can be violent and brutal as they are loving and altruistic. She came to understand them not only as a species, but as individuals with personalities, complex minds, emotions and long-term bonds.

It was confronting when Jane first witnessed their violent behaviour. “I thought they were like us but nicer and lo and behold they’re the same, though we’re worse because we can plan it all out deliberately. They just do it when the moment arises, and they get fired up.”

When it was a question of the professors telling her she’d done everything wrong, she very quietly went on writing about the chimpanzees the way they were. Then “luckily” her then husband Baron Hugo van Lawick’s film began to circulate and people in science began to change their view. “I don’t confront people, I just quietly go on doing it because I think people have to change from within,” she says.

To date what she started in Tanzania has continued and is one of the four longest unbroken studies of animals, now in its 64th year. Goodall returns twice a year to check that everything is going okay and to encourage field staff and students. She stays in the house on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, South of Burundi that she built in 1972 and lived in until 1986. Today, in rough weather, the water comes up to the steps. She also has a little house in nearby Kigoma where the foundations are underwater.

It’s a little too soon to know exactly how climate change is affecting the chimpanzees. “We do know that some foods are not ripening in the regular pattern they used to. The rains come very irregularly. It does get hotter in the hot season and can be dry in the wet season. But it will be a bit longer before we see how the chimps have changed their behaviour because they’re very adaptable. If the food they expect isn’t ripe, they’ll forage around and find something else.”

Being vegan

Unsurprisingly Goodall is vegan. She became vegan in 1970 after reading Peter Singers book Animal Liberation.

“I didn’t know about factory farms so the next time I looked at a piece of meat on my plate I thought, ‘this symbolises fear, pain and death. No thank you’. Then I learned about the treatment of dairy cows and laying chickens. I can’t be totally pure travelling around the world. I probably wouldn’t get enough to eat.

My son, who’s in Rwanda building environmentally-friendly houses makes sure that I’m taking this supplement or that vitamin. He’s a real bully,” she laughs.

One thing she didn’t find amusing was when New Zealand hit international headlines for all the wrong reasons in 2012 when Uruti School in Taranaki held a best-dressed possum competition which saw dead possums dressed in different costumes, including a bride and groom pair, which she describes as “horrible and sick”.

“Possums may be invasive but killing them and dressing them up and seeing how many they can kill is dangerous because it deprives the child of empathy, which I think most children have. But if they’re taught to be cruel, that’s a very dangerous thing, and we know that these animals have feelings and emotions.”

Legacy

Looking back, advice she would give her 40/50-year-old self would be exactly the same as what her mother told her; ‘Work hard, take advantage of every opportunity and don’t give up’. “There’s no better advice and I take that all around the world, especially to young people in disadvantaged communities, especially girls. I wish Mum was alive to know how many people have said, ‘Jane,

I really want to thank you. You taught me because you did it and I can do it too’.”

Looking ahead to what excites her most, she’s not sure. She knows what concerns her the most. Rising temperatures, loss of species and the war in Gaza.

“What excites me the most? I suppose finding out what happens when my body collapses. I don’t know what’s going to be the next adventure. I don’t think we just disintegrate. I may be wrong, but it doesn’t matter. If there’s nothing, I won’t need to worry, will I.”

And she remains hopeful because she’s been lucky enough to meet enough incredible people tackling the impossible and working on renewable energy as well as through the Jane Goodall Institute Roots & Shoots Programme, and to see enough amazing projects where nature will come back if given the chance.

Her goal is to grow the Roots & Shoots youth programme, which is now in 70 countries. “What they’re doing is changing the world so I want to grow that. I’m trying to raise an endowment so that when I’m gone, the work will be able to carry on.” And jokes that she may look down from somewhere to check that everybody’s doing what she wanted them to do. “I don’t know what I’ll do if they’re not but I’ll find a way.”