Coal contributes to climate change, carbon pollution and the destruction of natural habitats—it also heats homes, pays bills and lets me bend steel. Since I use coal everyday on the blacksmithing course I thought I’d better see where it comes from.

Many of us have never been to a coal mine or even use coal on a regular basis. But on the coast it’s a fixture of daily life. Good blogger Nate Savill goes looking for the source

The best coal in the world comes from the West Coast, and there’s a real beauty in these black nuggets that sparkle and shine. The coast’s identity has been built on natural resources and boy, they’re hanging on to coal, especially with the native logging industry gone. Coal heats homes, pays bills and lets me bend steel … and then there’s climate change, carbon pollution and the way its extraction destroys natural beauty. Not to mention that I use coal everyday on the blacksmithing course I attend, so I thought I’d better see where it comes from.

Following the trail of the buses which daily carry hundreds of men and women in blue and orange coveralls, we traveled into the mystery of the misty hills. I felt apprehensive remembering a description of the mine which ended with: “I didn’t think we did things like that in New Zealand”

So I made a tour up to the Stockton Coal Mine, the heart of Westport and the place which fuels the hopes and dreams of a community. Following the trail of the buses which daily carry hundreds of men and women in blue and orange coveralls, we traveled into the mystery of the misty hills. I had a fair idea of what I’d see, and I remembered a description of the mine which ended with: “I didn’t think we did things like that in New Zealand.” I felt apprehensive.

I once worked at a gem and mineral show in Arizona, where dealers fibbed about how the stones were “gently urged from the earth.” Here it looks like the coal is extracted by methods not unfamiliar to modern warfare. The mine site looks like it has been bombed; the landscaped is covered with huge holes and piles of rubble. Massive machinery slowly grind their way along rudimentary roads, slow and steady like the tanks on the evening news.

If I understood the tour guide correctly, charges are detonated deep in the earth, loosening the rock above the seam of coal, then massive bulldozers and diggers move the rock aside until the seams of coal are exposed. Indelibly embedded in my mind are the images of a huge digger gouging away at the black walls of an equally huge hole and dumping its load in a massive dump truck. It seemed so careless, so savage, devoid of skill and the romance of old miners and their lamps. It felt like greed and gluttony, and it looked like madness.

Outsiders like me want to go poking around and ask questions and change things, but if anything changes it’s got to change for the locals first

The birds are gone; the snails have been deported to live in fridges, and even the replanted tussock doesn’t seem to like the place. Still, the tour guide is adamant that one day all this will look like it did before the coal was removed. Paradise will be restored! The tour is part of Solid Energy’s PR campaign, the same one that ran a competition a few months back asking children to explain the role of coal in New Zealand’s sustainable future. The charade continues.

Many of us have never been to a coal mine or even use coal on a regular basis, but for the coast it’s a fixture of daily life. We hear about its contribution to global warming and pollution and habitat destruction. But here it’s not so simple; coal represents employment and security, overriding the environmental issues. Outsiders like me want to go poking around and ask questions and change things, but if anything changes it’s got to change for the locals first.

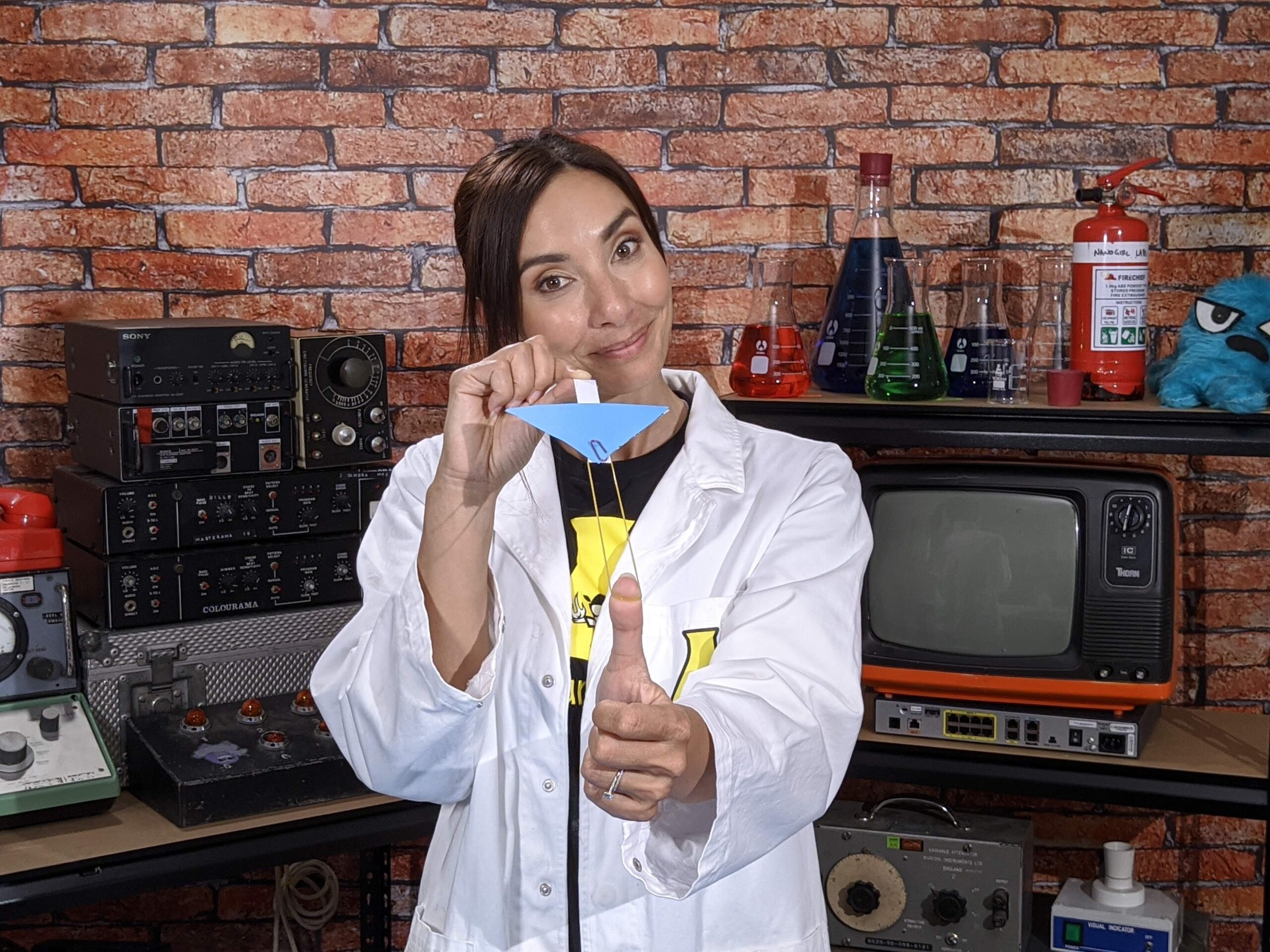

I’m confronted by the beauty of coal, the sparkle of rainbow colours in its jet black, smooth surface, as well as the dirty side: the black grit, the toxic smoke; the memories of the mine. Here in Westport, at the forge, we make beautiful things with that coal, and if we don’t treat the coal and its fire right, that same coal will ruin our work. It’s an almost personal relationship and it seems somehow restorative, like this is the way coal should be used, and for now that eases my mind.