Just get off the couch, exhort countless articles on weight loss and fitness. Since when did the humble sofa become the enemy of health and happiness? Rebekah White takes another look.

Seismic life shifts usually need a catalyst – sometimes a big one. Like when at the age of 24, Wallace Chapman discovered he had an incurable blood disease. Although he’d been a runner, the disease destroyed a hip, leaving him unable to walk long distances, and forcing him to reconsider his priorities. “I decided that I really had to make the most of my life, and I decided to do this by slowing down,” Wallace recounts in his new book, Don’t Just Do Something, Sit There (Penguin 2013). “I began thinking about reshaping my circumstances, taking what I had, breathing more deeply, sitting still, watching the clouds and decluttering my life. On my quest for information about a new, gentler way of living, an entirely new world opened up to me – the philosophy of the slower life.” The journey took Wallace out of a period of depression and unemployment and into his roles as a television personality and host on RadioLIVE.

For others it’s the epiphany of a moment, such as when British journalist Carl Honoré spied a book titled 60-Second Bedtime Stories and briefly thought ‘What a great idea,’ before recoiling in horror. It was a turning point that eventually led to his bestselling book, In Praise of Slow.

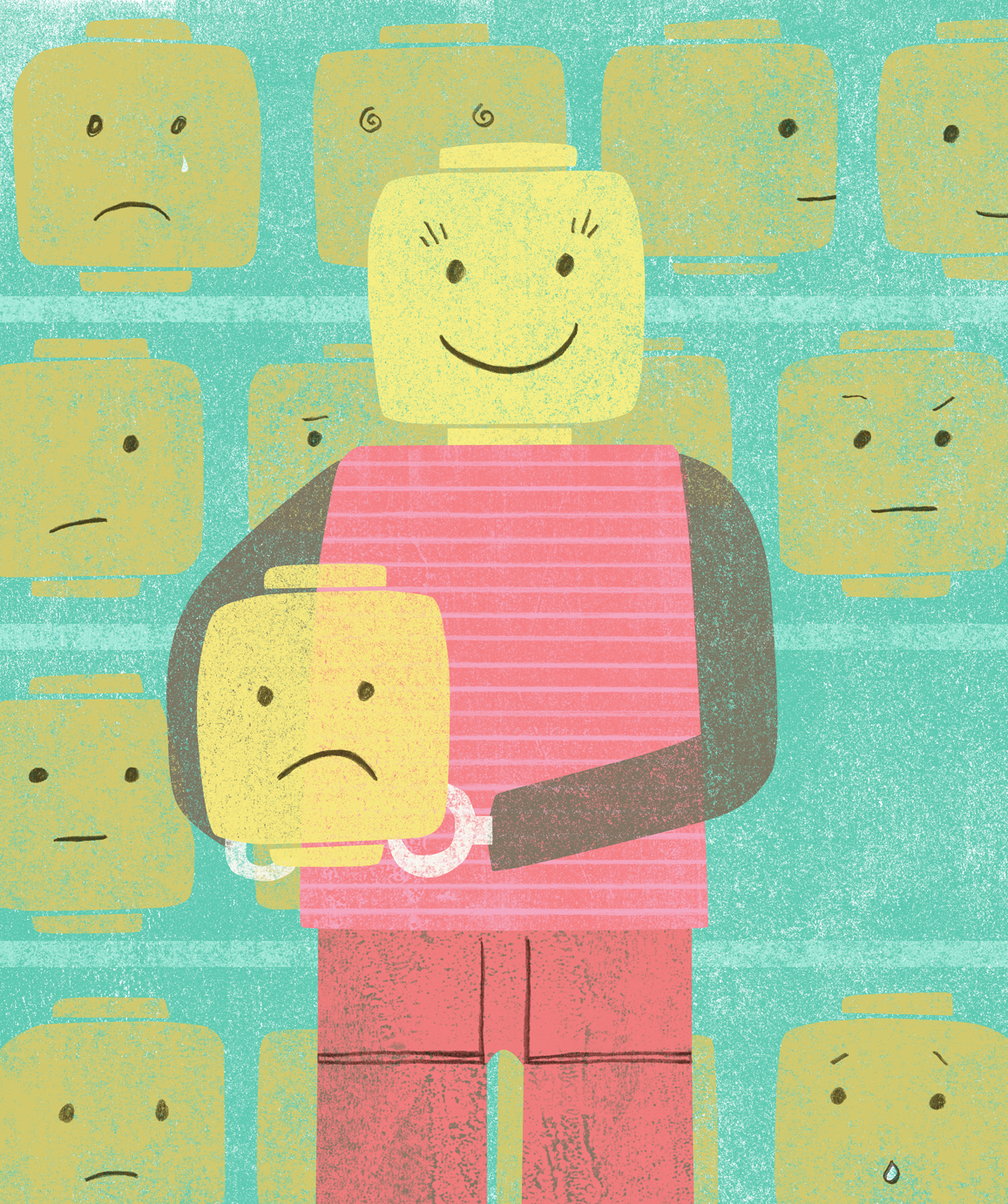

The Slow movement is a peaceful protest against modern culture. It acknowledges that the expectations we have of our lives, and what we ought to accomplish, are more complex and exacting than ever before.

What’s your mental checklist? A fulfilling career, well parented kids, fancy home-cooked meals, the fitness levels of a Hollywood wannabe, an on-trend wardrobe – and being a dab hand at a smoky eye? Or do you hold close a different, equally ambitious, list of life to-dos?

Coming up behind is the next generation – armed with a bunch of motivational acronyms to help them fit stuff in. Thoughts of ‘I don’t feel like going out tonight,’ are dismissed with ‘YOLO!’ (‘You only live once’), or a dose of FOMO (‘Fear of missing out’). But perhaps we’re so determined to carpe diem, we’re in danger of missing the point. What if seizing the day doesn’t mean cramming it so full that it starts coming apart at the corners? Could it be that satisfaction is to be found in smaller, humbler places?

The Slow movement challenges the notion that if you’re not busy, you’re settling for less, or letting experiences slip through your fingers. Slow values narrow and deep knowledge over the broad and shallow kind. It understands that some things just shouldn’t happen quickly. Be it slow gardening, cooking or loving, its followers around the world share a belief in things that are painstaking or time-consuming. They know that health and happiness don’t have instant makeovers. Relationships aren’t made in a day, or maintained in five-minute increments. You can’t learn a new skill without putting in time and effort – and bedtime stories shouldn’t be over in 60 seconds.

Turns out, winter’s the perfect time to rediscover the joys of doing less. As the days ebb, the evenings darken and the weather closes in, the body naturally gravitates towards a slower pace. It’s a welcome change from summer’s high-energy, activity-packed months, a time for inner restoration and, whether you are outdoors or in, for enrichment of a quieter kind. Here’s how to get started.

A midwinter night’s daydream

From Aesop’s Fables to Cinderella, we’re taught that lazing around is for losers – and villains. Idle hands make the devil’s work. Sloth is one of the seven deadly sins. Slow is a synonym for stupid. Even the English language thinks busy is best. Our words for ‘doing nothing’ all have negative connotations – they’re about shirking rather than relaxing. And our more poetic terms for lying about are synonymous with being lost in a mental fog: indolent, lethargic, torpid, languorous.

Yep, English is missing a word. One you’d use to describe time spent sitting on your front veranda with a cup of coffee, watching warblers and tui come and go, and the shadows getting shorter. Or an evening in front of the fire as it burns down, turning thoughts over in your mind to consider them from all angles. You’re not lacking in energy and you’re not in a stupor; you’re carefully observing the world around and within you. You’ve just stopped doing.

And your brain is far from lazy when you’re doing nothing. According to a study published in Nature journal, a brain scan of the idle mind reveals it’s almost as active as when completing complex mental tasks. Where once researchers believed the brain edited and encoded memories only while asleep, they now suspect the mind grabs any moment of downtime to get started on sorting through everything it has collected. “The brain at rest is not at rest,” said Harvard neuroscientist Alvaro Pascual-Leone in Newsweek magazine. “Even more important, this resting activity is not random, but is well organised and constitutes the bulk of the brain’s activity.”

Activities commonly frowned on as lazy are highly restorative and healthy: sleeping in, napping, wandering, gazing into the middle distance, daydreaming, people-watching. But if you normally lead a busy life, it’s likely you’ve got an inner critic demanding you spend your time ‘productively’. You may have to fight against feeling guilty for partaking in a bit of nothing – but it’s worth it.

“I’ve always liked the analogy of the mind as a muddy bucket of water,” says Wallace. “If you’re always moving the bucket, then the water will stay muddy. But if you leave the bucket still, the mud will settle and the water will become clear.”

Ideas for slow starters

Do without time one day a week. Don’t put on your wristwatch; ignore the clocks and go by the pace of the day. “Don’t think of time as rigid; understand it as a construct,” suggests Wallace.

Practise the noble art of sleeping in. Don’t get up the first time you wake, but let yourself drift in and out – and follow this up by lazing around in bed. As Tom Hodgkinson points out in his book How to be Idle, this activity was beloved by a roll call of big noters from the past, including Cicero, Horace, Milton, Swift, Rousseau, Voltaire, Trollope, Mark Twain, Robert Louis Stevenson, Proust, Collette and Winston Churchill.

Rainy Friday nights are the perfect backdrop to an hour or two of letter-writing, says Wallace. Imagine “the absolute joy of going out to the letterbox and seeing a letter from a friend – you just can’t believe it”.

Furnish your home with a comfy reading corner, including a blanket to curl up in, a side table for tea or hot chocolate and a directed light source. If home isn’t somewhere you can read undisturbed, find a cafe, library or scenic spot to park and settle in for an hour with a book.

Despite being New Zealand’s own slow living champion, Wallace Chapman’s days aren’t exactly filled with cloud-gazing or long walks on the beach. And he’s quick to emphasise that Slow living doesn’t necessarily mean lying around. Wallace sees it as a series of habits or a mind-set that can be used to mitigate the effects of a full, demanding life – which for him involves jetting between television and radio shows, speaking engagements – and running his street style blog. “I’m quite a busy guy – if I didn’t practise things like mindfulness or keeping a routine I’d go crazy. I’d get very stressed out,” he says. “Breaking the day into small steps and enjoying those small steps is how I get by.”

Mindfulness isn’t meditation, Wallace points out. “I don’t have the patience for meditation, my mind can’t turn off like that. But with mindfulness it can. Being in the present negates everything that’s happened in the last 24 hours.”

Wallace’s other favourite Slow habit is an oft-maligned one: routine. “Routine is wrapped in connotations of boredom, of tedium – but I love routine and it’s the way I’ve managed to forge my life,” he says. “If you have those anchors in your working week, you can deal with instability and unpredictability really well … I love going to my local cafe and seeing the barista yet again for the fourth time in a week.”

For Wallace, Slow living is ultimately about regaining connectedness and community. “The moment you start cutting yourself off from others, that’s when it starts breaking down.”

The art of ambling

In the 19th century, young Parisians who aspired to be hip would practice flânerie: the art of the stroll. The flâneur was a solitary figure, ambling aimlessly through the city’s streets while observing them keenly. The point was not to get anywhere but to notice everything along the way. Novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac described flânerie as the “gastronomy of the eye” – the best way to fully appreciate the richness and detail of city life.

On the other side of the channel to Paris’s urban spectators were England’s romantic poets, absorbed in the patient task of observing the natural, rather than the urban, world. Nature was considered to be the lens through which what was essential to life became clear. And it was through contemplating the outdoors that Wordsworth, Keats, Blake and others experienced their connection to the sublime.

Whether your roaming is urban, suburban, rural or international, Slow travel is a way of savouring the unique flavours of each place, rather than rushing from sight to sight.

There’s something to be said for pausing to observe a scene for long enough that the big things fade and small details reveal themselves. “Sometimes people travel great distances to see things which would probably lie neglected and unconsidered if they were under their noses,” wrote British philosopher Anthony Grayling in his book The Meaning of Things. “That suggests one should inhabit one’s life like a traveller, curious and alert, looking for the strangeness in things in order to seem them afresh.”

Ideas for slow starters

- Uncover your inner poet and go on a long, rambling walk. With good conversation along the way, it’s easy to wander for an hour or more. Stop regularly to observe what’s around you. On the beach? Take a look in any rock pools. In the bush? Identify plants or birds as you go. In the city? Choose to walk along streets you’ve never been down.

- Start a nature journal and aim to add something to it on each walk. Collecting specimens or stopping to sketch flora and fauna is an excellent way to focus on something you might otherwise miss.

- Clear winter nights are perfect for stargazing. Rug up, pack a hot drink in a thermos and find a park or hilltop. Bring a tarp so you can sit or lie on the ground without the bother of damp pants.

- Is the weather making the outdoors inaccessible? The poet John Keats thought humankind would be immensely happier if only they’d read a poem first thing each morning. Whether you agree with him or not, the works of Keats and his fellow romantic poets offer detailed, beautifully crafted portraits of the natural world.

At the table

The Slow movement began with food. In 1986, culinary writer Carlo Petrini led a protest against the opening of the first McDonald’s in Italy. It sparked debate about the way food culture was changing, which solidified into a mission: to preserve Italy’s legendary, deliciously slow (and increasingly beleaguered) dining traditions.

To Carlo Petrini, fast food represented a whole host of problems: poor nutrition, the loss of regional specialities, a lack of respect for the environment and the shattering of that cornerstone of social life – lingering over a shared meal.

Protesters couldn’t stop McDonald’s opening in Rome, but today the Slow food movement counts members in more than 150 countries and wields considerable political clout. Its adherents preserve recipes handed down through generations, rescue heirloom varieties of plants and seeds which have adapted over centuries to specific regions, and promote the ongoing production of artisanal and regional delicacies.

Slow food invites conversation: a weekend brunch, a leisurely dinner, or afternoon tea where the pot is refilled twice. And we’re programmed to eat together; even our word ‘companion’ comes from the Latin ‘with bread’. Research by the New Zealand government’s Families Commission confirms families who eat together not only enjoy healthier food but a greater sense of wellbeing, fewer instances of depression and better communication.

Slow food is as much about lingering around the table as what’s being dished up. It’s about taking the time for people to loosen up, relax and dig beneath the surface of everyday conversations – testing out differing views, receiving new ideas and forging relationships. Discussion around the family dinner table is how children form their opinions and understanding of the world.

Ideas for slow starters

On a rainy, chilly night, it’s easy to think ‘Oh, I’ll just get takeaways, I can’t be bothered,’ says Wallace. “But do be bothered!” he urges. “Winter’s the time for being bothered about making food at home.”

Forget cooking from a packet – you’re better than that! Learn to make your own basics such as tomato sauce, curry paste or stock and you’ll be amazed how much better it tastes.

Collect a recipe file of dishes your parents and grandparents used to cook. Make a favourite recipe your own by preparing it a number of times and experimenting a little around the edges. Give the dish, or cake, a personalised name and teach it to your kids. Did you know that Sally Lunn buns were first made in Bath, England by a woman of that name?

Bake bread from scratch. It’s not hard, but it requires a bit of hanging around as you wait for it to rise. Once you get the hang of a basic loaf, try pinwheel buns, brioche or pizza.

Create a routine involving a beautifully laid-out, scrumptious breakfast in the weekend which you linger over with a magazine or book. Visit the blog Simply Breakfast for inspiration.

Enjoy board games in front of the fire or heater. Lay a blanket on the floor and pull cushions off the sofa. Brew hot chocolate or mulled wine, and serve with biscuits straight from the oven, still on the cooling rack.

The creativity of downtime

For centuries there was a leisure class in the Western world so wealthy that they didn’t have to work. Politics of inequality aside, this group of people came up with loads of interesting stuff. As British philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote in his 1932 essay In Praise of Idleness: “It cultivated the arts and discovered the sciences; it wrote the books, invented the philosophies, and refined social relations. Even the liberation of the oppressed has usually been inaugurated from above.”

It’s not just competence in a chosen discipline, but an empty mind that sparks creativity – allowing us space to connect ideas in new ways. “Long periods of languor, indolence and staring at the ceiling are needed by any creative person in order to develop ideas,” says Tom Hodgkinson in How to be Idle.

Simple, repetitive tasks free the mind to roam and daydream, according to a 2012 University of California study published in the journal Psychological Science. Which is why crafts and creative hobbies rate highly on the scale of satisfying activities. They offer a balance of repetitive actions (kneading bread, cutting paper, practising piano scales) and creative expression (flavour combinations, greeting card designs, improvisation). You can’t do just one or the other; you need both.

And whether it’s pasta sauce or a knitted jumper that you end up with, there’s something deeply satisfying about being its creator. That’s because our brains are biased to like whatever we make – a human inclination identified by three professors from Harvard, Yale and MIT, in a 2009 study. The professors dubbed it the ‘IKEA effect’ after discovering that assembling even a few pieces of a kitset table brought more personal satisfaction than buying the same table already constructed.

So kick back, and get started on a bit of nothing – or another inefficient activity you’re keen on. You won’t be wasting time. You’ll be using it up properly.

Ideas for slow starters

Is there a hobby or activity you’ve always wanted to try? Cold nights are well suited to staying in and flexing your creative muscles or practising a new skill. Be it calligraphy, screen printing, preserving, learning to play a musical instrument or understanding a new language, there will be how-tos in books and no end of tutorials on YouTube.

Friends joke about reading Tolstoy’s doorstop War and Peace, but what if you actually did? Pick a classic novel you’ve always felt you should read and give it a go.

There’s a reason knitting has experienced a surge of popularity over recent years – it’s calming to the point of being meditative, and ridiculously slow. Knitting’s easier seen than read about, so if you’re just getting started, ask an experienced knitter for a one-on-one lesson.

There’s a reason we talk about ‘drawing’ from our experiences. Sketching is a sure-fire way to be in the moment and better observe the world around you. Check out the book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain for a step-by-step course anyone can follow.

Spend an evening listening to music the way it was intended to be heard – an album at a time. Whether by CD, iPod or record player, resist the temptation to multitask or opt for random shuffle. Instead, stretch out on the sofa and focus on the sound as you might if you were at a concert.

Ponder your next step in life. “June and July are career-planning months for me,” says Wallace. “I get out a bit of paper and write down a couple of short-term goals for January and February.” Start now before the end-of-year rush.