We read up on e-readers

Which has the greatest impact: a traditional paper book, or an endlessly refillable electronic book-like device? Scott Bartley reads up on e-readers

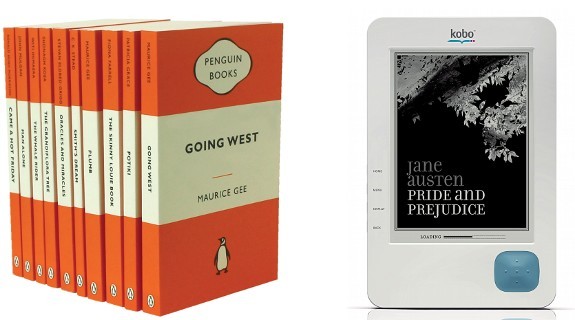

E-readers are on the way. Those sleek, portable slabs of battery-powered plastic and glass allow us to store entire libraries of books in our backpacks. Slowly, ever so slowly, the humble paperpowered book is being shoved into obscurity—or is it?

For now, many of us still find something wonderfully comforting about the look, feel and even the smell associated with reading a book (there’s also a certain reassurance in knowing its batteries will never die). But such hopelessly impractical feelings will surely dwindle as the generations pass, and there’s no denying the impact digital technologies are already having on our media consumption rituals.

Whatever the future holds, right now those of us looking to make the most environmentally friendly decision for feeding our book-buying habits are faced with a tricky choice. Do we opt for the read-once book made of recyclable paper? Or do we choose the considerably harder to manufacture e-book reader, with its concoction of potentially toxic materials, which can be used thousands of times?

When it comes to manufacturing, e-readers are the outright losers in terms of the raw materials required. A recent New York Times article on the subject estimated it takes almost 15 kilograms of minerals to produce a single e-reader (most of which is actually by-product that ends up as waste in a landfill), with some of the trace elements thought to be mined in wartorn areas of Africa. Such claims highlight the incredibly long line of resources that must be mined and refined from all over the planet in order to build a modern-day electronic device. The same article points out that printed books use under a kilo of minerals, most of which are used to build the roads required to distribute the materials.

But traditionalists shouldn’t get carried away just yet. The key to the argument lies in the reusable nature of e-readers. A report by the Cleantech Group, based on Amazon’s Kindle (which uses technology and components remarkably similar to those used in the Kobo reader, available from Whitcoulls in New Zealand), found that if someone who buys three books a month switches to an e-reader, in the space of four years they would save over a tonne of CO2. Even less voracious readers need purchase only 22.5 books over the life of the device for it to be a lower carbon option than purchasing those same books in printed form.

These figures take into account such things as jumping in a car and driving to a bookstore every time you purchase a book (or, if you order online, the cost of shipping that book to your door), and even the energy used by your reading light.

It’s also worth remembering that even if you’re no longer buying paper books, it doesn’t mean they’re not being printed, warehoused and distributed. Bookstores often find themselves with unsold stock that must be returned and, eventually, recycled. E-books suffer no such indignity: the whole supply and demand scenario is effectively wiped out, since it costs no more to produce 1,000 copies of an e-book than it does one. Mind you, if your e-reader dies after a couple of years or you decide to upgrade to a newer model, then you’re starting from scratch with your environmental savings, so it’s even-stevens really.

All things considered, e-readers may be the most environmentally sound choice for your personal carbon footprint under a certain set of circumstances—but it’s not a clear-cut win.

Plant a few extra trees and we can carry on reading our books and magazines without a shred of guilt—and the planet, not to mention our bookshelves, will look a whole lot prettier into the bargain.

Scott Bartley; research by Rebekah White