As fathers, parents and communities, we are constantly navigating how to best support our boys as they grow. Childhood naturally turns into adolescence, and adolescence into adulthood. These transitions are inevitable. The question is whether they will happen with intention, guidance and support or whether our boys will be left to figure them out alone.

This is where rites of passage come in.

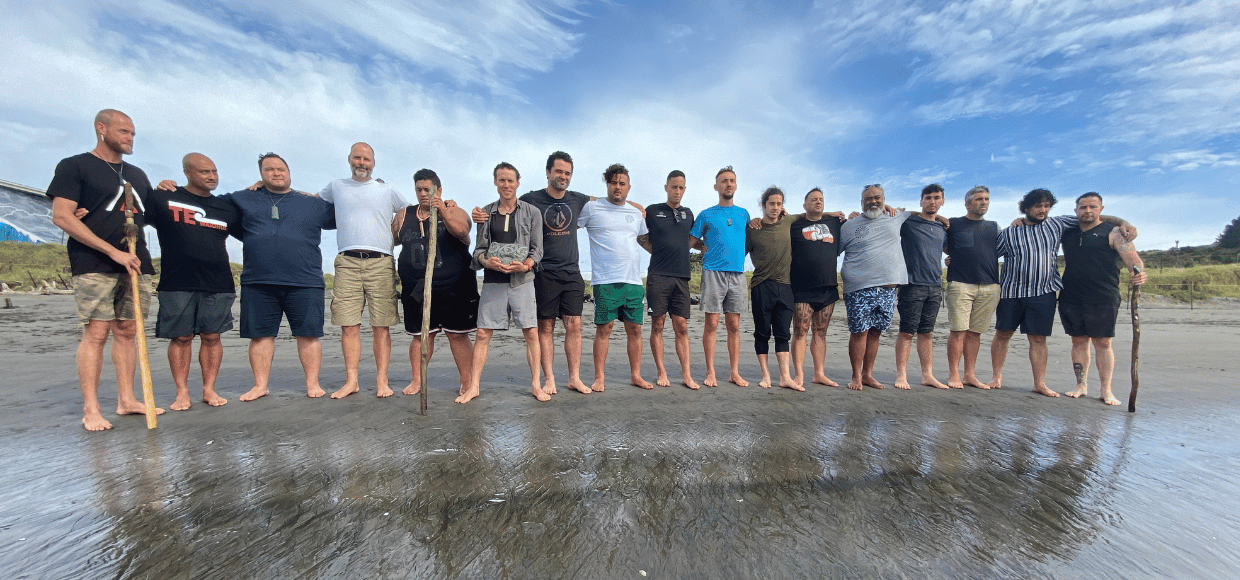

I had the privilege of speaking with Tiaki Coates from Poutama Rites of Passage, whose work is dedicated to reviving and reimagining this ancient yet urgently relevant practice. Our conversation highlighted why these transitions matter, how fathers and communities can step up and what happens when we don’t.

Rites of passage as markers and makers

When I asked Tiaki about the meaning of rites of passage, his response was striking:

“Rites of passage act as both a marker and a maker – they define the transition from boy to man while actively shaping that transition to be clearer, safer, and more meaningful. Without intentional guidance, young men will inevitably seek out their own rites of passage, whether healthy or harmful.”

He explained that boys are going to transition into manhood regardless. The only question is how. Without mentors and guides, young men often turn to risky behaviors or dangerous peer-led experiments to prove themselves.

As Tiaki put it:

“The critical difference is leadership. When we don’t provide structured pathways, boys create their own – often through risky behaviours, gang initiation, or other dangerous means. Instead of being guided by experienced elders who understand the journey, they’re led by peers in what becomes a case of the blind leading the blind.”

That image – boys leading boys through one of life’s most crucial thresholds – stays with me. It underlines the urgency of stepping into leadership roles as fathers, mentors and community members.

Remembering what was lost

In te ao Māori, and across Indigenous traditions worldwide, rites of passage were once integral. Colonisation, however, stripped much of this away. Yet Tiaki reminded me that wisdom hasn’t disappeared completely.

“Intentional, community-led rites of passage have been almost entirely lost through generations of colonisation. The recorded mātauranga about traditional rites is limited, but the guidance from tohunga and elders who support us is clear: we must do this work, and re-learn and re-member as we go.”

At Poutama, they draw inspiration from pūrākau, traditional stories and legends that act as blueprints for transformation. For example, Māui’s journey from rejection to heroism offers a timeless map of resilience, struggle and triumph.

Tiaki also shared how connecting with Indigenous communities around the world has revealed universal principles. Whether in Native American traditions or Aboriginal rites in Australia, cultures across the globe recognize the same need: structured, supported pathways into adulthood.

“These connections remind us that this need is fundamental to human development, not unique to any one culture.”

The role of fathers and male mentors

For Tiaki, the central ingredient in all of this is mentorship.

“Male mentorship is the central pillar of this work. Aotearoa – and seemingly the whole world – currently faces a massive shortage of mentors and good men who are intentionally guiding boys into healthy young manhood.”

He explained that, traditionally, this wasn’t the sole responsibility of fathers. Boys were guided by uncles, older brothers and elders. Fathers would farewell their sons, then welcome them back after their journey. That shared responsibility provided multiple perspectives and stronger community ties.

But in our world today, many boys don’t have fathers present, and many lack positive male role models at all. As Tiaki noted:

“It’s incredibly difficult to learn anything in life without a guide, teacher, or role model – imagine trying to learn to drive without an instructor, or play rugby without a coach. Yet we expect boys to navigate the complex transition to manhood entirely alone.”

The absence of mentorship, he says, is one of the most critical missing pieces in men’s health. Without it, boys learn about masculinity from sources that can be destructive – social media influencers, toxic online communities or equally lost peers.

When boys stay boys

The cost of neglecting this work is immense.

“Without proper initiation, boys never fully embody healthy adult psychology and remain trapped in boy psychology within men’s bodies. This creates enormous risks for our communities and the wider world.”

Tiaki described boy psychology as self-centeredness, emotional reactivity and avoidance of responsibility. These traits are natural and even healthy in children, but destructive when carried into adulthood.

We only need to look around to see what he means: leaders chasing power for themselves, men unable to manage emotions, families fractured by selfishness.

“Traditional rites were specifically designed to support the transformation from child psychology into healthy adult psychology – learning to use power in service of others, taking responsibility, managing emotions wisely, and understanding your role in the larger community.”

In other words: without rites of passage, we end up with boys in men’s bodies. And society pays the price.

How families can mark milestones

This work isn’t reserved for large community rites, it can also be woven into family life. Tiaki explained that the universal process is simple: separation, transformation, reintegration.

“Any family or community can create meaningful transitions by understanding and applying these principles.”

He offered a practical blueprint:

- Separation: Take the young person out of everyday life – this could be a camping trip, a weekend retreat or even device-free time at home.

- Transformation: Offer challenges and learning, whether physical, cultural or through deep conversation and service.

- Reintegration: Celebrate their return with acknowledgment, new responsibilities and recognition of their growth.

The essence isn’t ceremony for its own sake, but intention. It’s about creating sacred time and space where transformation is honoured.

Fathers healing while guiding

One of the most beautiful insights from Tiaki is the idea that fathers don’t need to be “perfect mentors.” Many men never had a rite of passage themselves. That doesn’t disqualify them – it actually opens a door.

“This is perhaps the most crucial part of the picture – men really need to go through their own transformation first to authentically hold space and help their boys make the transition. That’s why we offer mentor training and rites for men alongside our work with youth.”

He spoke about the tuakana-teina model, where roles between elder and younger can shift. Fathers don’t need all the answers. They simply need humility, willingness and honesty.

“We don’t want the ‘I’ve got it all sorted’ mentor. We want the ‘I’m here for you, I’m willing to share my story and hear yours, and we can figure this out together’ mentor.”

In fact, this vulnerability can be transformative for both father and son. Many men who engage in rites alongside their boys discover healing for their own unprocessed wounds.

What about single mothers and separated parents?

Not every boy has his father present. Many are raised by single mothers or in families where parents are separated. How, then, can these boys be supported?

The answer lies in community. Mothers can’t replace the role of male mentors, but they can play a crucial part in creating opportunities and connections. That might mean seeking out trusted uncles, grandfathers, coaches or organizations like Poutama.

The role of the mother is often to hold the sacred container – ensuring her son knows that his transition matters, helping him access spaces with strong male role models and affirming his journey. Fathers who live apart can still participate by showing up at key moments, marking milestones with intention and offering their blessing.

Even in situations where the father is absent or unavailable, the combination of a mother’s support and the presence of healthy men in the community can provide the scaffolding boys need.

Stories of transformation

The real power of this work lives in the stories. Tiaki shared two that illustrate what happens when boys are given the space and support to step into their next chapter.

About Mana, he told me:

“Mana had no positive male role models in his life – his father left the whānau when he was around three years old. Mana had carried the belief that his father’s departure was his fault and blamed himself for his younger siblings having no father figure… During our wānanga exploring the story of Māui, Mana shared his story for the first time. A large group of men were able to affirm that his father’s leaving wasn’t his fault, and supported him through both words and ceremony to let go of this destructive belief. Mana emerged from the rite renewed, fresh, and enlivened.”

And then Mauri:

“Mauri is 16, nō Ngāti Porou, living with his grandparents after losing his mother to methamphetamine overdose… After the four-day experience, Mauri shared that he felt he had truly ‘become a man’ and now had a ‘brotherhood from all around Aotearoa.’ Most powerfully, he said he was going to be a better tuakana, uncle, and mokopuna, and that one day he’d be ‘the best pāpā’ and be there for his kids.”

These stories are not abstract theories. They are lived proof that rites of passage change lives.

A vision for the future

Finally, I asked Tiaki to describe his vision of a society where rites of passage are honored. His answer felt like both a dream and a memory of something we once knew.

“Imagine Aotearoa alive with healthy men – positive male role models and community pillars on every corner. A safety net of loving, safe men woven throughout every part of our communities. Men embodying healthy adult psychology, using their power for the collective good, taking responsibility for themselves and their actions, honoring and respecting themselves, wāhine, and tamariki.”

He went further:

“Picture every boy knowing that when his time comes, there’s a pathway of greatness waiting for him… In this vision, we’d see dramatically reduced rates of male suicide, violence, and addiction. We’d have leaders who serve rather than dominate, fathers who are present and engaged, and communities where young people feel genuinely supported and valued.”

Bringing it home

For me, this conversation underscored something simple yet profound: raising boys into healthy men is not just the job of fathers. It is the work of families, communities and cultures.

The milestones – becoming a teenager, leaving home, stepping into fatherhood – should not be left to chance. They deserve to be recognised, marked and celebrated with intention.

Because when we honour these transitions, we do more than support individual boys. We weave a stronger, safer, more connected community for us all.

Find out more or to enrol by contacting [email protected]